Baseline assessment of oral health needs among underserved populations in the United States

*Corresponding author: Toluwani Adekunle, Department of Research and Development, Oral Health Programs, INC, Munster, Indiana, United States. toluwayne@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Adekunle T, Mbonu CB, Ogunjimi A, Alade A, Awotoye W, Kikuni M, et al. Baseline assessment of oral health needs among underserved populations in the United States. J Global Oral Health 2023;6:38-42.

Abstract

Introduction:

There are numerous inequities in access to oral healthcare in the United States (US). Lower utilization of oral healthcare services, a higher burden of dental diseases, and poorer dental outcomes are more prevalent among US immigrants compared to US-born populations.

Study Sample:

A sizable population of people in Iowa are immigrants. These immigrants are from democratic republic of congo (DRC), Eritrea, Burma, Bhutan, Burundi, Ethiopia, and Afghanistan. Iowa Refugee Assessment Report of 2018 shows that dental ailment is the second most prevalent condition among new entrant refugees. As a result, the Oral Health Programs targeted an oral health intervention at US immigrant populations.

Objectives:

This report aims to highlight significant findings from the baseline survey to further understand the needs for oral healthcare amongst immigrant and underserved populations in Iowa. This intervention utilized community peer educators to sensitize and mobilize immigrants to better access dental services. Training modules were developed for the volunteer peer educators and educational materials were translated into the native languages of the most populous refugees (French, Swahili, and Arabic). The Oral Health Program implemented a community health campaign, developing a questionnaire to capture demographic information, knowledge, awareness, barriers to uptake of dental check-ups/oral assessment,s and preferred sources of information. Preliminary findings indicated the need for increased awareness about oral health.

Findings:

There is a need to leverage existing social safety net programs to deliver oral health information and foster connections between dental service providers and their target populations. This study has shown the need for continued efforts towards increasing oral healthcare among underserved ethnic/minority and immigrant populations in Iowa. Future interventions need to focus on improving access and removing structural and social barriers to dental/oral care.

Keywords

Oral healthcare

Digital oral health campaign

Underserved

Immigrants

INTRODUCTION

Despite significant improvement in the oral health of US populations since the 1960s, there are still inequities in the access to oral healthcare.[1] In the US, poor oral health is a marker of social inequities within the general population.[2] Vulnerable populations, such as low-income, immigrants, racial/ ethnic minorities, and refugees, are often more likely to experience oral health concerns.[2] Lower utilization of oral healthcare services, a higher burden of dental diseases, and poorer dental outcomes are more prevalent among US immigrants compared to US-born populations.[3-5]

A sizable population of people in Iowa are immigrants.[6] The American Immigration Council (2020) estimates that this population is about 4%, with up to 538 newly arrived refugees into the US settling in Iowa in 2018.[6] These immigrants are from DRC, Eritrea, Burma, Bhutan, Burundi, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, etc. The majority are from DRC and Eritrea (54.8% and 13.8%, respectively).[6] Iowa Refugee Assessment report of 2018 shows that dental ailment is the second most prevalent condition among new entrant refugees. Some of the reasons for these include the fact that newly arrived refugees face language and cultural barriers and lack knowledge of the US dental healthcare system. Weak financial standing and lack of health insurance are other impediments to accessing dental care.[7]

Iowa provides dental benefits to refugees through the dental wellness plan (DWP), the state Medicaid program. The DWP requires enrollees to complete “Healthy Behaviors,” which include oral health self-assessment and preventive dental checkups during the 1st year to keep full benefits in the next year. Previous evaluation of the DWP program shows that 66% of beneficiaries did not know about the healthy behavior component of the DWP program.[8]

The coronavirus disease-19 pandemic worsened the above situation by limiting access to general healthcare from both the provider and user sides. On the one hand, the healthcare workload increase and the burden posed by the infection control procedures, significantly reduced access to oral healthcare. On the other hand, hesitancy and fears over the pandemic and job losses among immigrants have combined to reduce dental healthcare-related visits.

DESCRIPTION OF THE INTERVENTION

As a response to the burden of oral healthcare needs among immigrant and underserved populations in Iowa, Oral Health Programs implemented a community health campaign. This intervention utilized community peer educators to sensitize and mobilize immigrants to better access dental services. Training modules were developed for the volunteer peer educators and educational materials were translated into the native languages of the most populous refugees (French, Swahili, and Arabic).

This intervention seeks to increase preventive oral health services uptake among African refugees in Iowa City. The proposed theory of change is that by increasing the knowledge and skill of African refugees/immigrants to fulfill the healthy behaviors requirement of the DWP, more refugees will qualify for the full dental benefits, which will increase utilization of preventive oral health services.

This intervention applied the social cognitive theory (SCT) to create a social network that will raise awareness of and promote utilization of oral health services. SCT describes a dynamic, ongoing process, in which personal factors, environmental factors, and human behaviors influence one another. According to SCT, three main factors affect the likelihood that a person will change their behavior: (1) self-efficacy, (2) goals, and (3) outcome expectancies. If individuals have a sense of personal agency or self-efficacy, they can change behaviors even when faced with obstacles. If they do not feel they can exercise control over their health behavior, they are not motivated to act or persist through challenges. This report aims to highlight significant findings from the baseline survey to further understand the needs for oral healthcare among immigrant populations in Iowa. A questionnaire was developed to capture demographic information, knowledge, awareness, barriers to uptake of dental check-ups/oral assessment, and preferred sources of information.

RESULTS FROM THE BASELINE ASSESSMENT

Demographics

Country of origin, Length of stay and Household income

Participants of this study were from the following countries: [Table 1]: Democratic Republic of Congo (27%), Nigeria (24%), Ghana (15%), Tanzania (3%), Kenya, (3%), Ivory Coast (3%), Zambia (3%), USA (3%), Mexico (3%), South Africa (3%), Liberia (3%), Morocco (3%), Italy (3%), and Libya (3%).

| Country of origin | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 27 |

| Nigeria | 24 |

| Ghana | 15 |

| Tanzania | 3 |

| Kenya | 3 |

| Ivory Coast | 3 |

| Zambia | 3 |

| USA | 3 |

| Mexico | 3 |

| South Africa | 3 |

| Liberia | 3 |

| Morocco | 3 |

| Italy | 3 |

| Libya | 3 |

Participants in this study had varying length of stay in the US (healthcare utilization patterns of immigrant populations may vary widely based on their length of stay in the US. Very often, the longer the length of stay, all factors being equal, the more similar health seeking behaviors of immigrants may be to that of individuals within the host country. Some of this is due to acculturation and access). Length of stay in the US by participants in this study as shown in [Table 2]: born in the US (9%), less than 1 year (12%), 1-5 years (26%), greater than 5 years but less than 10 years (32%), and greater than 10 years (21%).

| Length of stay in US | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Born in US | 9 |

| Less than 1 year | 12 |

| 1–5 years | 26 |

| Greater than 5 years but less than 10 years | 32 |

| Greater than 10 years | 21 |

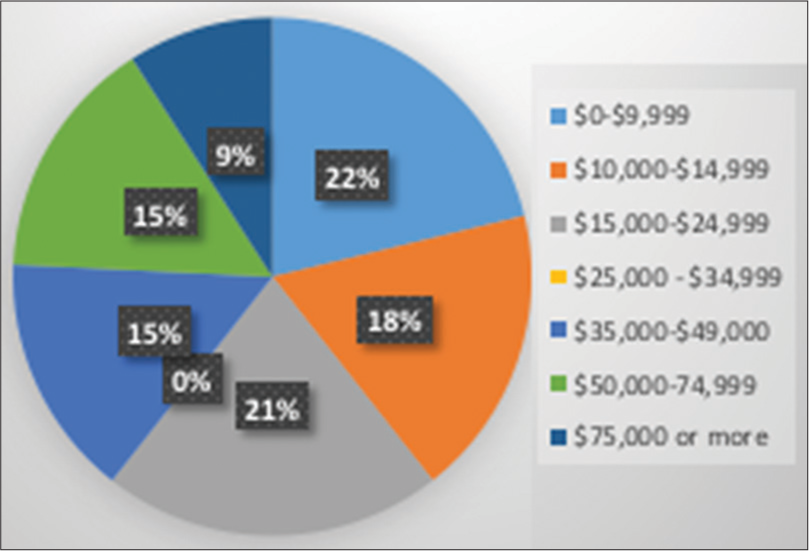

Participants in this study reported varying household income levels, as shown in [Figure 1]. The three highest income bracket recorded by study participants are as follows: $0-$9999 (22%); $15,000-$24,999 (21%); and $10,000-$14,999 (18%).

- Proportion of participants’ yearly household income.

Type of dental Insurance coverage

Participants in the study had a variety of dental insurance coverage. Sources of dental care for participants [Table 3] are as follows: Employer (28%), Medicaid (19%), marketplace health insurance (14%), directly from insurance company (14%), and through a government program that is not medicaid or medicare (6%). Out of the study participants, 14% reported that they had no dental care.

| Type of dental insurance | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Employer | 28 |

| Did not have dental care | 19 |

| Medicaid | 19 |

| Through a health insurance marketplace or exchange |

14 |

| Directly from insurance company, not through marketplace |

14 |

| Through government programs other than Medicaid/Medicare |

6 |

Knowledge

Have you heard of dental wellness plan (DWP)?

No (63%), Yes (37%)

Have you heard about healthy behaviors program (HBP)?

No (74%), Yes (26%)

Uptake of oral self-assessment/dental check-up

Did you complete the oral health self-assessment within the last year?

No (76%), Yes (24%)

Did you get a dental check-up within the last year?

No (40%), Yes (60%)

In the past 12 months, was there ever a time when you needed to see a dentist but you could not go to one?

No (49%), Yes (51%)

Perceptions about annual dental check-ups

Getting a dental check-up each year is important to you, strongly agree (72.4%), agree (24.1%), and neither agree nor disagree (3.4%). If you complete a dental checkup, you are less likely to have problems with your teeth, strongly agree (59%), agree (28%), neither agree nor disagree (7%), and disagree (7%). Getting a dental checkup each year is beneficial to you, strongly agree (76%), agree (21%), and neither agree nor disagree (3.4%)

Barriers to completing oral health assessment/dental care

What prevented you from completing the oral health self-assessment screening “I wasn’t aware I was supposed to complete the oral health self-assessment” (21%). “Don’t know/not sure” (17%), “I did not think it was important” (6%), “I forgot” (6%), “I do not have internet access” (2%), “The oral health self-assessment was too long to complete” (2%), “I didn’t know how to return it to the dental clinics” (2%).

What prevented you from getting a dental check-up?

I do not currently have a dentist (35%), I’m not sure where to go to get a dental check-up (26%), it is hard to get an appointment for a dental check-up from the dentist (17%), other (17%), getting transportation to my dentist’s office is hard (3%), I do not like getting a dental check-up (3%). In the past 12 months, was there ever a time when you needed to see a dentist but you could not go to one? Why? Too expensive (26%), lack of dental insurance (28%), not sure of where to get services (8%), I am embarrassed about my teeth (4%), fear of dental treatment (2%), experience with dentist or staff (2%), and other (4%).

Preferred sources of information

Where do you go to find information about local news, events, or announcements in your area?

Social media (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) (38%), TV (23%), friends and word of mouth (18%), (12%) newspaper/ prints (12%), and radio (8%)

How many times a day do you look at social media?

10+ times a day (43%), 3.5 times to 10 times a day (27%), 2–3 times a day (17%), once a day (10%), and not everyday (3%)

What social media networking site do you use?

Facebook (25%), Instagram (23%), Snapchat (20%), Twitter (16%), WhatsApp (11%), Pinterest (4%), and Tumblr (1%).

DISCUSSION

Oral health is important for the holistic well-being of individuals.[2] In this study, 63% and 74% had not heard about the DWP and healthy behaviors program (HBP), which is indicative of the need for an increase in targeted awareness and educational programs for underserved and immigrant populations of the participants had not heard about the DWP and, which indicates the need for increased educational awareness programs for underserved and immigrant populations in Iowa. This finding is in accordance with Reynold’s (2018) finding on low levels of awareness of the HBP component of the DWP in Iowa. When assessing for oral self-assessment and dental check-ups, we found that while fewer people (76%) were engaging in oral health self-assessment, more people (60%) reported that they had engaged in dental check-ups within the last year. Particularly, 21% of the study participants did not know that they were supposed to complete the oral health self-assessment. This may indicate the need for increased awareness about the oral health self-assessment option.

In the study population, 51% had experienced a time when they needed to see a dentist but could not go. This shows the presence of underlying barriers to oral healthcare for the target population. The previous studies have identified barriers such as affordability, low knowledge levels of the healthcare system, and difficulties in communication as barriers to oral healthcare utilization for refugee and underserved populations.[9] This intervention study sought to circumvent the barriers that the target population encounter while meeting their basic oral healthcare needs. More so, 35% of the target population reported not having a dentist; 26% reported that dental care was too expensive; and 28% lacked dental insurance.

Although only 19% of the sample population reported not having a dental insurance policy, aside from not having a dentist, other barriers to getting a dental checkup are not being sure of where to go (26%). This indicates that access, in the form of insurance coverage, is necessary but not sufficient in the utilization of oral healthcare services. Dental health interventions should endeavor to raise awareness about the dental services available to their target population. This study showed that most of the target population (72%) perceived that an annual dental check-up is important; more than half of the population (59%) agreed that people who engage in regular dental check-ups are less likely to have problems with their teeth; and 79% strongly agreed that yearly dental checkup is beneficial. These findings show that the perceptions of oral health among the target population are mostly positive.

It is important to identify approaches that can help enhance the delivery of oral health information. Specifically, within immigrant communities, it will be beneficial to leverage existing social safety net programs to deliver oral health information. Studies have shown that immigrants with a moderate network size were more aware of the importance of dental care and were more likely to use dental services. Conversely, a poor social network (that is a network with few individuals with knowledge of dental health) was inversely related to negative oral health outcomes.[10] With respect to communication, 38% use social media to get information. Approximately 70% used social media between 3.5 and over 10 times a day. This project will need to look for innovative approaches to harness the potential of social media to spread information about oral health services. Another caveat will be to develop oral health information that is language appropriate. This assessment also highlighted access to care as a major challenge, 61% of the respondents did not have a dentist or could not get a dental check-up mainly due to the lack of knowledge on where and how to access dental care, cost of dental care, lack of insurance, and difficulty getting an appointment for a dental check-up among others. Thus, campaign activities on oral health should not only provide information about oral healthcare, but should also point clients to places where care can be sought.

CONCLUSION

This study has shown the need for continued efforts toward increasing oral healthcare among underserved ethnic/ minority and immigrant populations in Iowa. The baseline assessment shows low levels of knowledge about the basic oral health programs that are available to the general population, indicating the need for an increase in awareness of these programs. While most of the target population had dental care coverage, many of the study participants did not have a dentist, which is a common phenomenon among the target population in other contexts. This also reinforces that access is necessary, but not sufficient in improving oral healthcare among immigrants, ethnic/racial minorities, and underserved populations. This study did find more positive perceptions about dental/oral care among the target population. This allows for future interventions to focus on improving access and removing structural and social barriers to dental/oral care.

Findings from this baseline assessment indicate the need to increase communication campaigns and raise awareness about holistic dental care among immigrant populations. Campaigns should focus on using digital platforms, including social media outlets, to deliver messages about oral health to the target population. These campaigns could either be delivered in person or using social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. As such, interventions should endeavor to improve communication and follow-up between providers and patients, to help increase the rate of completed oral healthcare.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Delta Dental of Iowa.

References

- Disparities in Oral Health. 2021. United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/oral_health_disparities/index.htm [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 12]

- [Google Scholar]

- Disparities in access to oral healthcare. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:513-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Use of dental services by immigration status in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147:162-9.e4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disparities in oral health by immigration status in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149:414-21.e3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challenges in the provision of healthcare services for migrants: A systematic review through providers' lens. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:390.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immigrants in Iowa. 2020. Available from: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/immigrants_in_iowa.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 12]

- [Google Scholar]

- Refugee Health Program Annual Report 2018. 2019 Available from: https://www.idph.iowa.gov/portals/1/userfiles/206/idph%20refugee%20health%20report%202018.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 12]

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of enrollee satisfaction with Iowa's Dental Wellness Plan for the Medicaid expansion population. J Public Health Dent. 2018;78:78-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriers and facilitators to dental care access among asylum seekers and refugees in highly developed countries: A systematic review. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:337.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caregiver’s social relations and children’s oral health in a low-income urban setting. Soc Sci Dent. 2010;1:77-87.

- [Google Scholar]