A comprehensive exposition of the synergistic collaboration between the public and private spheres in healthcare

*Corresponding author: Dharmashree Satyarup, Department of Public Health Dentistry, Institute of Dental Sciences, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. dharmashree_s@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Panigrahi P, Satyarup D, Nanda J. A comprehensive exposition of the synergistic collaboration between the public and private spheres in healthcare. J Global Oral Health. 2024;7:119-24. doi: 10.25259/JGOH_2_2024

Abstract

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) are a type of partnerships between the government and the private sector. PPPs promote innovation in healthcare by combining the resources of the public and private sectors. They provide advantages such as improved service, enhanced accessibility, and cost savings. However, they also have drawbacks such as divergent goals, hesitancy, influence imbalances, and limited data. This review focuses to examine types of PPP in healthcare such as service contracts, operations, maintenance contracts, and capital projects, with a focus on their diverse applications and impacts, its benefits, efficiency, cost-effectiveness, challenges, divergence goals, issues about prices, disputes, and the influence of private sector on healthcare quality, access, and costs in Indian scenario. The review also provides a comprehensive and globally relevant exploration of PPP in healthcare, with a special focus on dental care, non-clinical services, and pragmatic insights into its challenges and solutions, offering a valuable resource for stakeholders in the field.

Keywords

Cost-effectiveness

Health

Innovation

Partnership

Stakeholder

INTRODUCTION

A nation’s health is pivotal for its economic and social growth. As the population ages and technology advances, global healthcare spending has increased. Governments prioritize health in the Millennium Development Goals by employing public–private partnerships (PPPs) to enhance healthcare access. PPPs are vital to access, quality, and cost control and provide a platform for collaboration among governments, the private sectors, and stakeholders.[1] However, this comes with challenges that include different goals, public reluctance, private-sector influence, and performance data gaps. India’s healthcare spending is significantly lower than that of the global, developed, and other similar emerging economies and is less than half the global average in percentage terms as compared to “percent of gross domestic product (GDP)” of other countries [Figure 1].[2] Private investments might be crucial in bridging infrastructure investment gaps due to the limitations the government may face. Public–private healthcare partnerships have the ability to raise service standards, lower costs, and broaden access to treatment. In addition to providing services, medical equipment, technology, and staff, it may be used to fund, construct, and run healthcare facilities. Fostering greater cooperation between public and private sector actors can enhance the effectiveness of healthcare systems.

- A comparison of healthcare spend in 2010 according to the World Health Organization World Health Statistics.

India faces a significant healthcare divide, with only 27% of the population residing in metropolitan regions; yet, these areas host a disproportionate 75% of the country’s healthcare infrastructure. This leaves them with insufficient access to primary healthcare facilities. Recognizing this disparity, the government allocated approximately 845 billion Indian rupees to health expenditure in the fiscal year 2022. Notably, around 274 billion Indian rupees were dedicated to the National Health Mission (NHM). Looking ahead, the government budget estimates an increase, with total health expenditure expected to surpass 891 billion Indian rupee (INR) by fiscal year 2024. The allocation of resources reflects a commitment to bridging the healthcare gap and addressing specific health issues.[3] The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare not only formulates policies for public health but also tackles issues such as nutrition deficiency, demonstrating a comprehensive approach to improving healthcare accessibility and outcomes across the diverse Indian population [Figure 2].[4]

- Health spending by government health expenditure and out-of-pocket expenditure (taken from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1343739/india-health-expenditure-by-majorhead.com).

METHODOLOGY

A thorough search of online databases, with a particular emphasis on Google, was conducted using keywords such as “public–private partnership (PPP)” and “India.” In PubMed, the search term employed was (((public) AND (private)) AND (partnership)) AND (India) to retrieve relevant articles. The selection process involved a manual review of all identified articles to ensure inclusivity and relevance.

Types of PPPs in healthcare: PPPs may be classified or described according to purpose, organizational structure, or scope of activity. Product-based partnerships, which enable it, include drug or product donation programs or bulk purchase of products for low-income countries and childhood immunization programs of vaccine purchases. According to product-development, the partnerships enable incentives for discovery and/or commercialization. Then, there is a system-based partnership that supports government efforts to strengthen health service delivery through health strengthening systems. An important example being is Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI), which is the Vaccine Alliance that forms a PPP which facilitates the collective purchase and distribution of vaccines for low-income countries, ensuring affordable access to immunization services. Based on the nature of collaboration, the government may collaborate with the private developer/service provider as a funding agency/buyer/coordinator. With a clear customer focus, PPPs enhance social services and facilitate the recovery of user charges. Particularly in healthcare, PPPs leverage technical expertise and incentivize performance-based monitoring, fostering quality improvements and technology transfer.[5]

Considering the advantages of public–private collaborations in healthcare, it entails a sustained partnership between the public and commercial sectors. Service contracts, operations and maintenance (management) contracts, and capital projects, including those involving operations and maintenance, serve as the three fundamental categories that can be employed to classify projects and programs within the realm of PPP. Strategies that are used to select the service provider can be through various biddings, like competitive bidding, which involves a well-publicized and organized bid procedure that evaluates the provider’s or developer’s financial, technical, and management skills. Another mode of selection is the Swiss Challenge Approach wherein the government requests suggestions from participants in the business sector.

Payments in PPP hinge on performance metrics, emphasizing efficiency and effectiveness. Private sector compensation options include contractual payments (down payments, progress payments, closing costs, annuities, and receivables guarantees), grants-in-aid (capital grants, institutional support, and block grants), and the right to impose user charges for cost recovery. PPPs involve risk and reward sharing, founded on risk and revenue-sharing principles. Project implementation risks cover delays, contractor defaults, and environmental impact. Legal risk encompasses changes in lease rights and security shifts. Addressing these diverse risks demands strategic management for successful PPP collaboration between the public and private sectors.[5] In the realm of PPP, various models facilitate collaboration for infrastructure projects, defining roles and responsibilities for efficient implementation [Figure 3].[6,7] Notably effective in India, the build–operate– transfer (BOT) model leverages private sector investment and expertise to mobilize finance, ensuring optimal construction, operation, and maintenance. BOT promotes efficiency and quality through competitive bidding, minimizing project costs. Private participation, guided by performance-based contracts, enhances accountability, incentivizing enterprises for efficiency and target-oriented outcomes. Crucially, the BOT model encourages risk-sharing, with the private sector assuming project risks. This collaborative approach harnesses strengths from both sectors, establishing BOT as an effective PPP in India to address infrastructure challenges, foster competitiveness, and ensure quality outcomes in public service and project delivery.[8]

- Several models of public private partnership.

Dental care and PPP: To ensure comprehensive oral health initiatives, a collective effort is needed to build the nation’s oral health infrastructure, catering to the public, private practitioners, and government employees. Collaboration between public health and healthcare communities proves beneficial for programs addressing both oral and general health, including food counseling, tobacco control, health education for expectant mothers, and support for oral protection in sports [Figure 4].[9] Private practitioners contribute by training paramedical personnel in primary health centers (PHC), community health centers, and rural health facilities, including village guides, dais, and Anganwadi workers. This collaborative framework showcases diverse contributions from the private sector in a holistic approach to enhancing oral health through PPP.[10]

- Scope of public-private partnership in dental care.

PPP in healthcare: PPPs have efficiently delegated basic PHC services, spanning healthcare, promotion, and prevention, including specialized areas such as family planning, environmental health, and maternal and child healthcare. Addressing health issues such as malaria and common ailments, PPPs ensure comprehensive and accessible community-level healthcare by harnessing resources from both sectors.[6] Globally, PPPs, widespread in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development states and middle-income countries, involve the public sector delivering crucial healthcare services, while the private sector manages infrastructure, such as hospital construction. Global alliances like the GAVI coordinate with individual companies, exemplified by the partnership with the Dutch energy firm Nuon through the foundation for rural energy services in Mali. In Indonesia, a PPP between the national family planning coordination board and private midwives and doctors, with initial start-up capital provided, showcases successful collaboration for family planning services. These instances underscore the multifaceted and globally significant role of PPPs in enhancing healthcare provisions.[3] PPPs are important in the development of health education and promotion activities that have a global impact [Figure 5]. In this way, PPPs have demonstrated their capacity to considerably enhance the services for infectious illnesses, demonstrating their potential to affect real change.[8]

- Examples of global programs through public–private partnership.

In India, notable initiatives spotlight the effective use of PPP in healthcare delivery, showcasing efforts to boost health awareness and services across various sectors. The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), established in 2005, stands as a model program dedicated to offering accessible and affordable healthcare to rural populations. NRHM actively engages in reproductive health programs, immunization efforts, and community health awareness projects. Collaborating under NHM, PPPs manage PHCs in states such as Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Manipur, Meghalaya, Nagaland, and Odisha. Non-governmental organization (NGOs) such as Shanti Maitri and Karuna Trust oversee operations, leveraging government infrastructure. Mobile Medical Units (MMUs) represent a pivotal area of PPP implementation, with 23 states and union territories deploying them, notably in Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan, each with over 100 MMUs. Urban MMUs are in the pipeline for cities such as Bhubaneswar, Cuttack, and Rourkela, aiming to provide doorstep healthcare in slum communities. These units, equipped with a comprehensive team, including doctors, auxiliary nurse and midwives (ANMs), pharmacists, and support staff, prioritize delivering accessible and quality healthcare. NHM’s PPP initiatives extend to emergency ambulance services, notably the dial 108/102 ambulance services. Dial 108 addresses critical care and trauma cases, while dial 102 focuses on basic patient transport, especially for pregnant women and children.[11,12]

Initiatives such as Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram and the free maternity entitlement scheme ensure comprehensive, cashless delivery services, and covering maternal and new-born care. The skill enhancement in emergency obstetric and new-born care initiative focuses on equipping healthcare providers with essential skills for effective obstetric emergency management. PPPs, exemplified by Free Diagnostic Initiative (FDI) computed tomography scan and FDI-tele-radiology, are pivotal in enhancing diagnostic services across states such as Andhra Pradesh, Meghalaya, and Rajasthan, demonstrating the diverse efforts under NHM to bolster healthcare services nationwide.[11] PPPs play a key role in diverse health programs, encompassing reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health (RMNCH+A) services and disease control initiatives. In family planning, efforts like the Merrygold scheme in Uttar Pradesh utilize voucher schemes and social franchising, establishing centers for contraceptives and counseling. Odisha’s PPPs, like the Ama Clinic, bring innovative healthcare to remote areas.

In the realm of disease control, the National Vector Borne Disease Control Program focuses on critical challenges, particularly in addressing malaria. India’s significant contribution of 83% to total malaria cases in the Southeast Asian region emphasizes the need for robust interventions. The Comprehensive Case Management Project in Odisha, a collaborative effort between the Government of Odisha, the Indian Council of Medical Research-National Institute of Malaria Research (ICMR-NIMR), and Medicines for Malaria Venture, successfully improved early diagnosis and treatment accessibility, detected numerous asymptomatic cases, and enhanced overall case management during the 2013–2016 intervention phase.[12] Initiatives like the Mukhyamantri Chakhya Yojana, coupled with the National Program for Control of Blindness, receive support through grants and aid for cataract surgeries. Through these multifaceted PPP engagements, India’s health landscape benefits from enhanced services, broader outreach, and more effective disease control mechanisms.[11,13]

The Pradhan Mantri National Dialysis Program collaborates with state governments and private entities, providing hemodialysis at the district level for both below poverty line (BPL) and above poverty line (APL) patients. Free dialysis is offered to BPL individuals, while APL category patients access services at discounted rates through open tendering. The government contracts private providers for institutional services, including C-sections and blood transfusions. Aarogyasri, launched in Andhra Pradesh in 2008, extends statewide, delivering critical treatment at private institutions for families below and above the poverty line, supported by government subsidies for premium claims.[14] The Karuna Trust, a non-profit operating in India and the United States, effectively manages 61 PHCs across six states. These initiatives enrich India’s healthcare landscape with diverse interventions for various societal segments.[3]

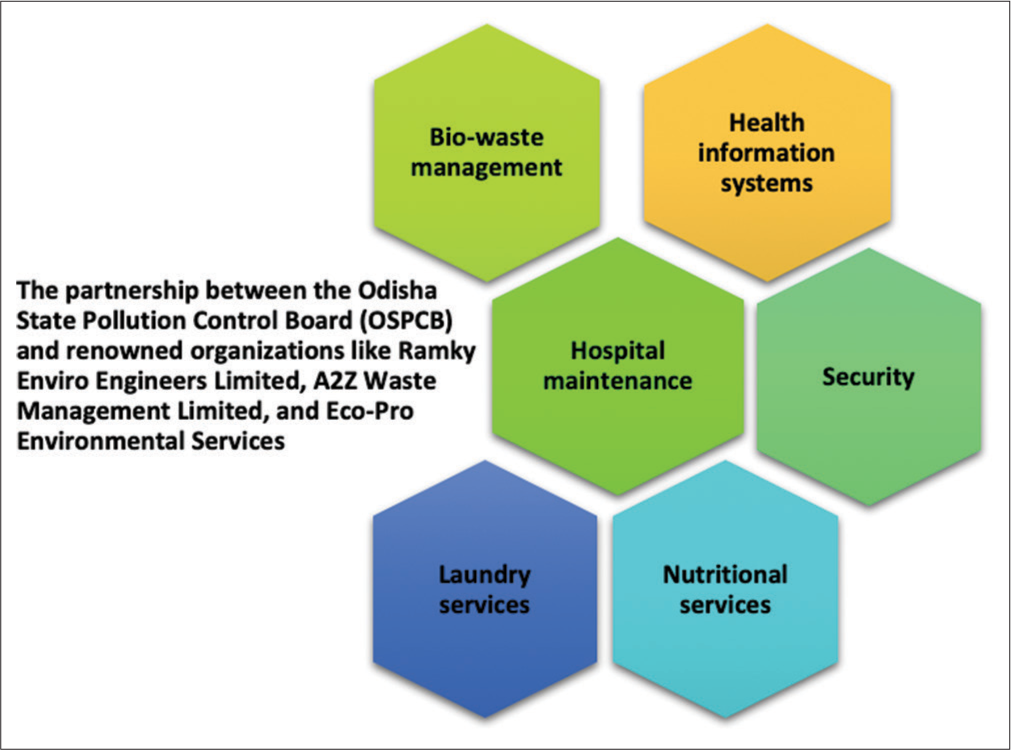

PPP in non-clinical healthcare: PPPs are pivotal in non-clinical healthcare services that include [Figure 6] outsourcing these services to for-profit organizations ensures effective management and specialized expertise exemplifies successful PPPs in non-clinical services. These collaborations facilitate efficient biowaste management aligned with environmental guidelines, enhancing operational effectiveness and sustainable healthcare practices.[9,10]

- Public-private partnership in non-clinical healthcare services.

PPP in oral healthcare: PPPs play a crucial role in advancing oral healthcare in India. Initiatives like Colgate Dental Health Month collaborate with schools and organizations, such as Smile India and the Swasth Foundation, to raise awareness and provide preventive dental care, especially in underserved areas. Mobile dental clinics, established through PPP agreements, creatively address dental health challenges in remote regions. The Mukhya Mantri Swasthya Seva Mission Oral Health Scheme in Odisha exemplifies successful PPP collaboration with private dentists to extend oral healthcare services to rural areas. Programs such as the Tobacco Intervention Initiative and Mumbai Smiles actively engage dental clinics in tobacco cessation and oral health awareness. The Brush Up Challenge and Live Learn Laugh Program, supported by Colgate-Palmolive, highlight PPPs’ role in promoting good oral habits and education. The “Bright Smile and Bright Future” initiative, supported by Indian Dental Association (IDA) and Colgate-Palmolive, trains Anganwadi workers to educate children in rural areas about essential oral care practices, fostering a collaborative approach to improving oral health across India.[9,10]

In emerging markets like India, current healthcare trends underscore the escalating importance of PPP. These partnerships play a pivotal role in addressing evolving healthcare demands, extending beyond the capacities of the public sector. As aging populations and the prevalence of diseases increase, PPPs emerge as a crucial solution for both infrastructure and service requirements. Government involvement is paramount in PPPs, providing vital support by creating positions for dentists in PHC, offering capital subsidies in the form of 1-time grants, and, in some cases, supporting projects through revenue subsidies, tax breaks, or guaranteed annual revenues for fixed periods. Recognizing these trends highlights the integral role of PPPs in shaping India’s healthcare sector, emphasizing collaborative efforts between the public and private domains for improved health outcomes.[12,13]

Implementing PPP in healthcare entails navigating various challenges that demand careful consideration [Figure 7]. A primary challenge revolves around selecting qualified providers and contractors, for which enforcing legislation like the Clinical Establishment Act (2010) becomes crucial. Managing the performance of contracted healthcare services adds complexity, requiring a holistic approach that considers the multifaceted nature of health outcomes and their dependencies on various factors. For instance, India collaborates with the private sector for rural healthcare, while the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the United States partner with private entities to serve low-income individuals. Navigating these dynamics demands a comprehensive understanding of the diverse factors influencing health outcomes.[14,15]

- Challenges encompassing range of issues in public–private partnership.

To navigate the complexities, a comprehensive approach involving stakeholder awareness, stringent safety measures, vigilant monitoring, and thorough evaluation is imperative for the success of such partnerships. While challenges persist, leveraging data for solutions and ensuring well-informed and engaged stakeholders can mitigate risks, leading to improved healthcare outcomes. Addressing PPP challenges involves collective efforts to balance interests, enhance communication, and commit to data-driven decision-making.[1,2,16-18]

Adapting global PPP examples, like Australia’s Medicare system, for India, involves implementing a universal healthcare model with robust government funding. India can aim for affordable and comprehensive medical services, drawing inspiration from Australia’s schemes. Strengthening public hospitals, prioritizing primary care, and fostering public–private collaboration can optimize resources for an effective healthcare system. Adaptations must consider India’s socioeconomic context and ensure public engagement for successful implementation.

Emulating the UK’s Private Finance Initiative hospitals could leverage private investments for healthcare infrastructure, addressing India’s gaps. Germany’s sickness funds system might inspire India to explore comprehensive health coverage through public and private contributions, fostering financial sustainability. Learning from Brazil’s Family Health Strategy, India could enhance primary care with community-oriented approaches. Emulating the US telehealth initiatives, India may embrace technology for remote healthcare delivery. Inspired by the Netherlands’ health insurance model, India can explore a balanced approach with private insurers, ensuring wider coverage. South Korea’s digital health infrastructure could guide India in developing advanced healthcare technologies for efficient service delivery. Each adaptation should consider India’s context and prioritize inclusive, accessible, and quality healthcare services.[19-22]

CONCLUSION

Governments all over the globe are favoring PPPs in healthcare as they provide the advantages of improved service accessibility, higher care standards, and cost savings. They are a sensible option for healthcare system updates aiding in reducing costs. Collaboration and effective public–private communication are essential. Ensuring accountability in the public sector is crucial, but when it is used properly, they provide innovations and new information. However, dealing with PPP necessitates strong cooperation, communication, and decision-making. It is essential to maintain transparency in the public sector and prevent conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent was not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Lessons from healthcare PPP's in India. Int J Rural Manag. 2020;16:7-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Review of key challenges in public-private partnership implementation. J Infrastruct Policy Dev. 2021;5:1378.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Government health expenditure in India FY 2022-2024 by major head. 2024. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1343739/india-health-expenditure-by-majorhead.com [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 05]

- [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable development of health in India: An inter-ministerial contribution towards health and wellbeing for optimum quality of life. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2021;44:19-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Partnerships in healthcare: A public private perspective In: Hosmac-CII Whitepaper. 2010.

- [Google Scholar]

- Public hospital facilities development using build-operate-transfer approach: Policy consideration for developing countries. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(12) Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.39866 [Last accessed on 2024 Jan 29]

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Public Private Partnership in India. Available from: https://www.pppinindia.gov.in [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 04]

- [Google Scholar]

- Public-private partnership to enhance oral health in India. J Interdiscip Dentistry. 2012;2:135-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Public private partnership'-Public private partnership: The new Panacea in oral health. Adv Dent Oral Health. 2018;8:555734.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Public-private partnerships in primary healthcare: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public-private partnerships in healthcare under the National Health Mission in India: A review New Delhi: The National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC); 2021.

- [Google Scholar]

- Public Private Partnership in Odisha. Available from: https://odisha.gov.in/investment-odisha/public-private-partnership [Last accessed on 2024 Jan 29]

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of public private partnerships in ensuring universal healthcare for India In: Universalising healthcare in India. Singapore: Springer; 2021.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- India could harness public-private partnerships to achieve malaria elimination. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2022;5:100059.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for operation and management of urban mobile health unit (MHU): Under PPP National Health Mission. Odisha. Available from: https://nhmodisha.gov.in/writereaddata/Upload/Documents/MANAGEMENT%20OF%20MOBILE%20HEALTH%20UNIT_final.pdf [Last accessed on 2024 Jan 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- Saving mothers and newborns through an innovative partnership with private sector obstetricians: Chiranjeevi scheme of Gujarat, India. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;107:271-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guideline on Primary Health Center (New) In PPP Mode India: National Health Mission, Government of India; 2020.

- [Google Scholar]

- Public-private partnerships for global health In: Kickbusch I, Ganten D, Moeti M, eds. Handbook of global health. Cham: Springer; 2021.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Public Private partnership in India: PPP Toolkit for improving PPP decision making processes India: Department of Economic Affairs-Ministry of Finance, Government of India; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- An overview with case studies from recent European experience In: Health, nutrition, and population family discussion paper. Washington DC: World Bank Human Development Network; 2006.

- [Google Scholar]

- An overview of public private partnerships in health. International Health Systems Program Publication. Harvard School of Public Health.

- [Google Scholar]