Translate this page into:

Oral health status of children in rural communities of Sri Lanka

*Corresponding author: Oariona Lowe, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, UCLA School of Dentistry Los Angeles, CA. lowedds@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Lowe O, McClellan D. Oral health status of children in rural communities of Sri Lanka. J Global Oral Health 2021;4(1):42-7.

Abstract

Social determinants of health are affected by socioeconomic status, level of education attained, living conditions, and access to healthcare. Access to oral health care is impacted by the environment, in which one resides and the knowledge and benefits of good oral healthcare and prevention, most of which is influenced by parental knowledge and habits. Oral health status was reported on two populations of Sri Lankan children; one group residing in a tea plantation and the other in Mullaithivu, the northernmost area of Sri Lanka. Tea estate dwellers represent an impoverished group, where the education level attained is less than half of the national average. The decay rate in this population of children is high, many of them with early childhood caries. In Mullaithivu, children make up one-third of the population. Children between the ages of 6 and 19 were observed to have a large number of caries. Access to dental care in these remote areas is limited. Developing an oral health program to serve these populations would be beneficial to assist in healthy living.

Keywords

Oral health

Dental caries

Access to dental care

Tea plantation

INTRODUCTION

Inequalities in global oral health are viewed in the context of global public health and local challenges.[1] Chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease are often studied but oral disease, specifically dental caries, which is that one of the most prevalent of all health conditions are often overlooked.[2-4] Interventions aimed at solving health inequalities continue to be studied by recognizing characteristics specific to countries worldwide. This knowledge will help to reduce the pain of oral disease experienced by children affecting their quality of life.[3,5] In addition to treating oral disease, creating and establishing interventions which would be effective in preventing poor oral health in certain populations need to be identified. Health gradients and inequalities persist due to socioeconomic (SE) status[6] which is measured by income, educational attainment, occupation, and race/ethnicity.[7,8] It is also influenced by social conditions, the environment, and the context, in which individuals live and make decisions about their health.[9]

This paper focuses on the prevalence of the oral disease in two different populations of children in Sri Lanka. One group included children residing in a tea estate in Nuwara Eliya, and the other groups were children from the Mullaithivu District. Although most oral diseases are preventable, untreated oral disease was observed in the majority of the children. This report addresses the poor status of children’s oral health in these rural communities of Sri Lanka, where access to oral health care is limited suggesting that an oral health program in these communities would be beneficial to improve the quality of life.

Background and rationale

Sri Lanka, formerly Ceylon, is a densely populated island country in South Asia. It is home to several ethnic groups, each with their own cultural heritage. Although largely a Buddhist nation, Hinduism, and Islam have influenced its religious beliefs.[10] The majority of its people live in rural areas and depend on agriculture for their livelihood.[5] The Sri Lankan economy is subdivided into three main sectors: Urban, rural, and estate,[11] the estate sector refers to tea plantations dwellers.[11] The history of Sri Lankan’s plantation industry is unique, where the living and working conditions of estate labor evolve around the objective of ensuring productivity, quality, and profit for the plantations.[12] The basic necessities of health care, housing, and education are available but limited.[12] The percentage of children who do not complete school in the estate sector is 11.3%, which is more than double that of the national average at 4.8%.[11]

Over one million Sri Lankans are employed in the tea industry, where 75–85% of the workforce are young women who represent the lowest social strata of the tea plantation social hierarchy.[12] Poverty levels on plantations have consistently been higher than the national average and, although overall poverty in Sri Lanka has declined in the last several years, poverty in the estate sector has been reported to be increasing with roughly one in three suffering from poverty.[13] Nuwara Eliya, the area plentiful of tea plantations, showed a significant increase in poverty among workers from 22.6 percent in 2002 to 33.8 percent in 2007.[13] In 2019, poverty rates in the plantation sector were 8.8% compared to 4.3% rural and 1.9% urban.[14]

Malnutrition among estate children is high.[15] Many of these children do not receive proper nutrition, and the child grows up to be malnourished with unhealthy diets.[15] Basic education is also lacking even though it is offered free.[15] The estate sector resident population reflects both ill-health and lacking education.[15] The average education level completed by the head of the household estate dweller is Grade 5.[13]

Estate housing consists mainly of back to back lines, single houses, and shanties.[11,13,15]

Six percent of the houses in the estate sector have no bedrooms.[11,15] As experienced in a 2016 visit to a family shanty, a single cooking pot was located in one area of the room which was the kitchen. Lighting was provided and emanated from a single light bulb hanging from the ceiling. The living quarters consisted of one room with a dirt floor covered by a carpet. The family was very proud of what they had. Local inhabitants of the tea estate were very friendly and kind, but many of them hid their smiles. The noticeable lack of oral health care by the plantation workers and their children was concerning and it was obvious that some suffered pain and discomfort from dental disease. Many covered their mouths hiding their smiles. The children had visible signs of decay and it was obvious that daily oral hygiene was not practiced. Many of the younger children had signs of early childhood caries (ECC). Children were breastfed and many times would fall asleep when feeding. They also consumed large quantities of sweetened tea at very young ages. Most of the estate children had never seen a dentist.

Rampant caries, tooth decay, and poor oral hygiene were observed in many of the children between 2 and 6 years old.

Mullaithivu

Mullaithivu is the northernmost region of Sri Lanka. In 2010, the population was 136,000,[16] by 2019 the population decreased to 97,000.[16,17] Children of various ages make up approximately one-third of the residents.[16] This area was devastated by a Civil war which lasted over 25 years resulting in over 100,000 deaths.[17-19] Many of the children were reportedly orphaned. Two-thirds of the population are below the age of 40 and the majority of this population are <19 years old.[18] Military personnel represents a large number of families here.[18] Children from the area have been without healthcare until recently when medical care has been provided on a limited basis.[20] Oral healthcare is lacking and the oral health needs of this population until recently has not been examined. Due to its remote location, access to dental care is limited, which is also affected by the lack of dentists residing in the area. There are only five dental surgeons in the General Hospital in Vavuniya.[18,21] Many of the children have never seen a dentist. Without adequate oral health care, children will suffer from dental pain. Untreated dental lesions lead to eating problems and malnourishment, speech problems, dental abscess formation, and infection which can ultimately cause death.[22] As children grow up and start families of their own, the population will expand, and the need to have established programs to provide adequate medical and oral healthcare services becomes paramount. Increased awareness of oral health will improve the dental and overall health of the people in this region. The ultimate goal is to provide access to oral health services to eliminate pain and suffering from oral and dental disease which could lead to more devastating health issues. This study shares the findings from the children examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A team of healthcare workers representing a non-profit NGO group from the USA collaborated with a non-profit group in Sri Lanka. The team was made up of two practicing pediatric dentists, one hygienist, and an administrative staff person from the USA and a Sri Lankan medical aide who was the interpreter. Between 2016 and 2019, the team visited a tea plantation in Nuwara Eliya and a beautiful coastal area on the Indian Ocean at the northeast corner of the island, Mullaithivu.

The two dentists from the USA worked together to develop a screening sheet that was used to collect data. Caries was noted as present or not present and affecting primary or permanent teeth. Information on oral hygiene practice and diet was also noted. With parental permission, oral health status was charted using the “open your mouth technique” and by observation using a tongue blade, gloved hands, and flashlight. The two examining dentists were calibrated using the same diagnostic tools. Gingivitis was noted by the condition of the gingival tissues as puffy, red, swollen gums with noticeable build-up of plaque, and calculus. Caries was noted as yellowish-brown and black areas and broken teeth.

The dental professionals examined 80 children from the tea plantation. These children were between the ages of 2–6 years old. Many of the children had ECC. ECC is defined as the presence of one or more decayed (non-cavitated or cavitated lesions), missing (due to caries), or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth in a preschool-aged child between birth and 71 months of age. Due to time restraints, only the presence of caries was noted.

From 2017 to 2019, approximately 800 children between the ages of 2–18 years old from Mullaithivu were examined. With parental consent, the same dental examiners using the same “open your mouth” and observation technique performed oral assessments. Equal numbers of male and female children were examined. Information gathered from parental interview indicated that the children did not clean their teeth regularly, and they consumed diets high in sugar and carbohydrates.

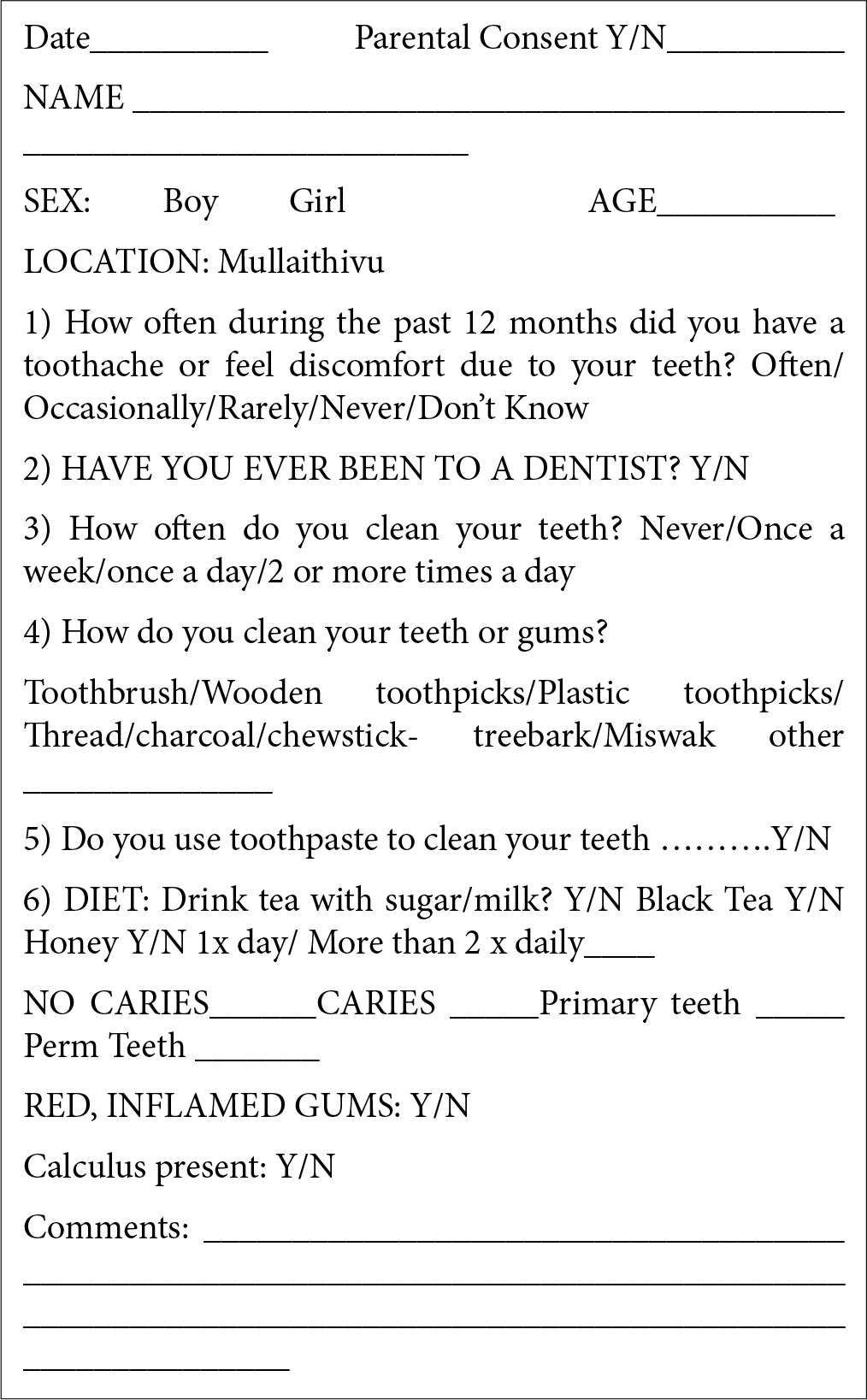

The oral assessment form used is shown in [Figure 1].

- Child oral assessment.

RESULTS

The data collected are descriptive and qualitative. No statistical analysis was drawn from the findings. In this report, a dichotomous classification of caries (caries versus no caries) was used and the data were strictly from observation.

Many of the children aged 2–6 years old residing in the tea estate experience ECC and tooth decay. Due to limitations from the tea plantation, no graphic data from this population are available. The estate children presented with a large amount of decay, ECC, and obvious lack of oral hygiene

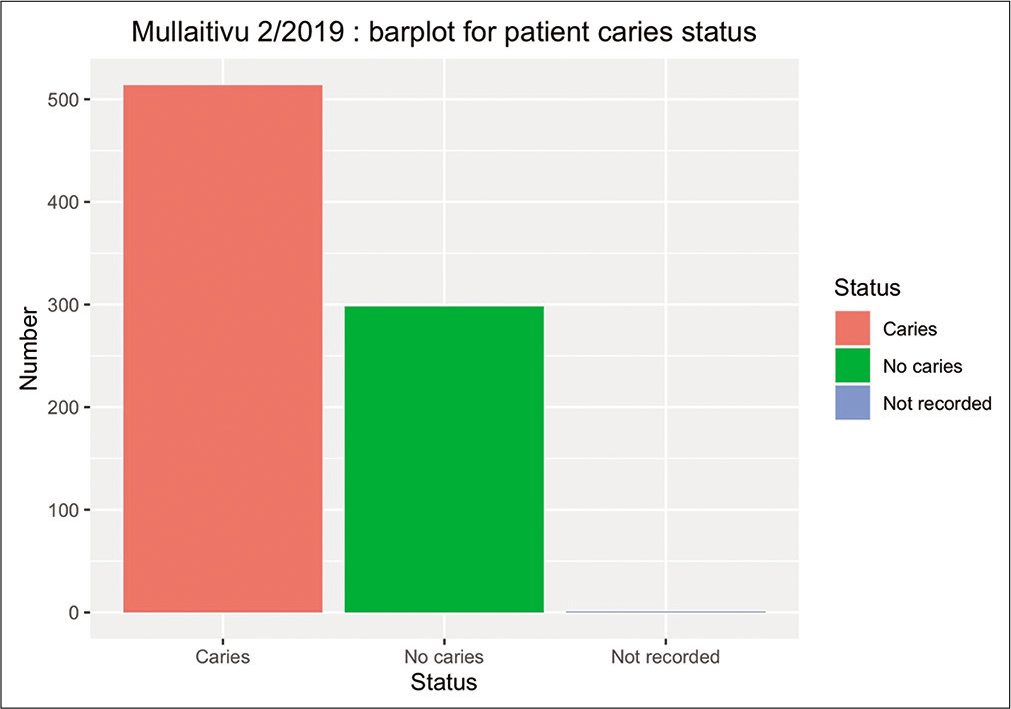

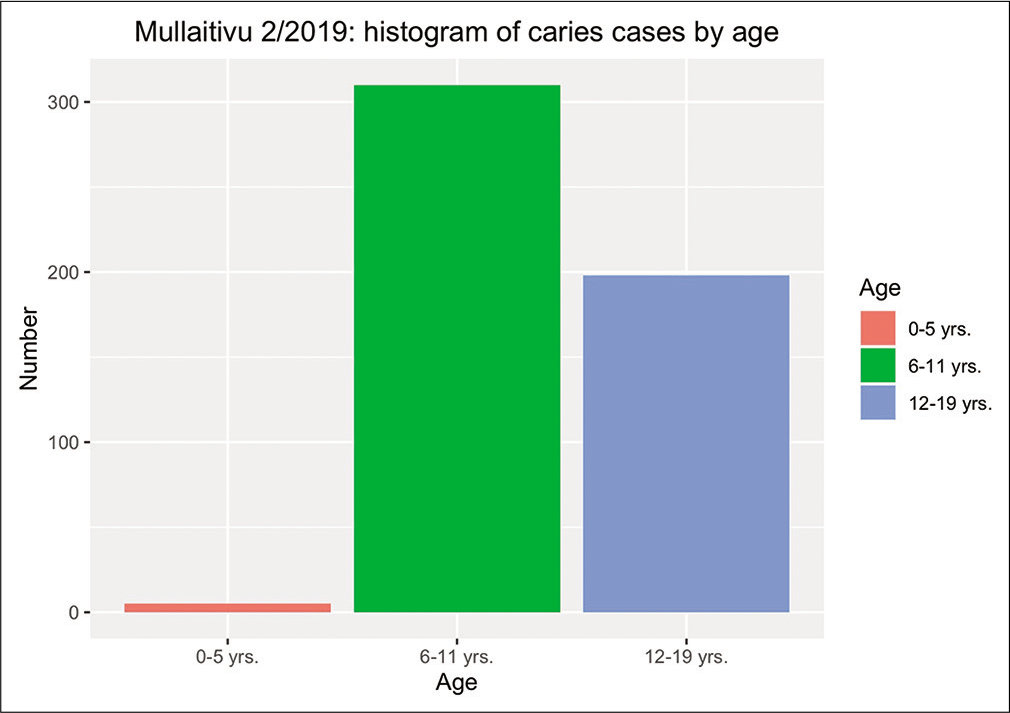

Preschool-aged (2–5 years old) children in Mullaithivu and the majority of elementary and high school-aged children (from 6 to 18 years old) had tooth decay. The first graph represents the number of children with and without caries [Figure 2]. The second diagram [Figure 3] shows the number of children in hundreds and by age who presented with caries

Sri Lankan teenagers in the Mullaithivu District had extensive decay to the permanent molars

The number of carious molars was not tabulated but only noted on the assessment form utilized

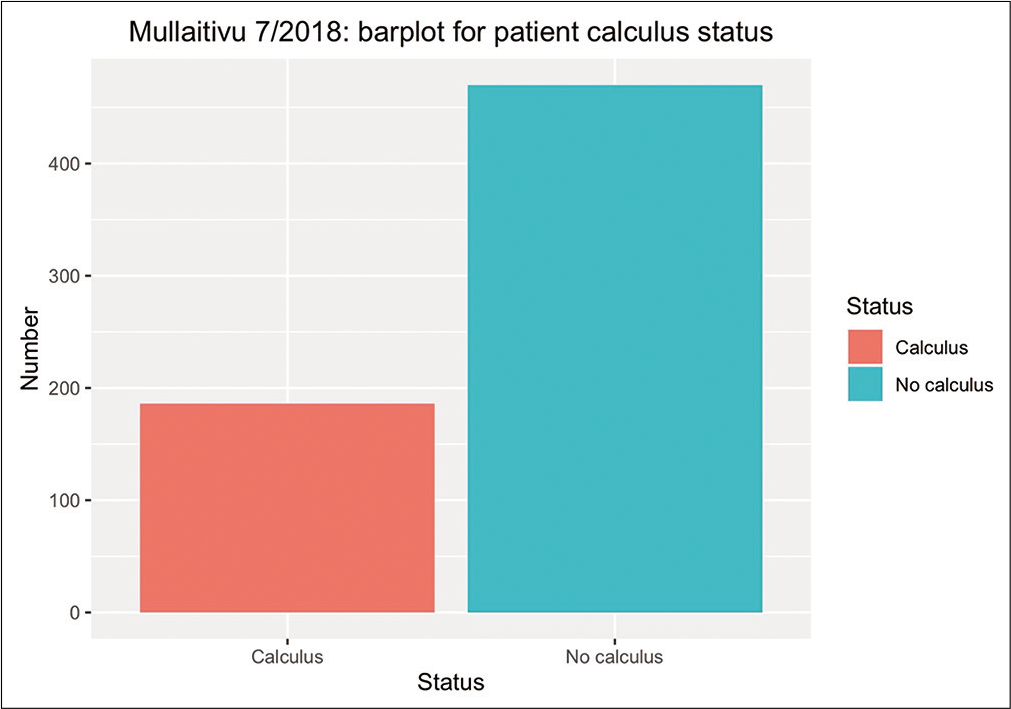

Gingivitis and calculus buildup were evident in older children (9–18 years old) and were also noted on the form. [Figure 4] shows the number of children who exhibited the presence of calculus in July 2018

Preventive care was lacking. Many of the children did not own a toothbrush and daily teeth cleaning was not practiced. The frequency of brushing was not tabulated although the question was asked and noted on the assessment form. Toothpaste was rarely used due to lack of supplies

Diet: The majority of the children consumed tea with sugar and milk or honey at least 3 times a day.

- Barplot for patient caries status.

- Histogram of caries cases by age.

- Barplot for the patient calculus status.

When asked, the children did not know how to respond to experiencing dental pain although it was obvious that some had pain because they would refuse to open their mouths and would not smile. The majority of them have never seen a dentist.

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Observations from the Mullaithivu district indicated that age, area of residency, as determined by school district, were important factors related to the presence of caries and untreated carious lesions. Older children were more likely to have untreated caries. The vast majority of the children from 2 to 6 years old residing in the tea estate exhibited ECC* and gross dental decay. This information can be used to develop programs to address dental problems specific to these areas. Habits begin during childhood, and the earlier children start to learn good oral habits, the greater the chance of living a healthy life. Practicing good oral care habits at home during child development and providing dental education at school will positively influence children’s health. Older children will make their own decisions and develop daily routines. Persistent poverty and low income may directly or indirectly affect children’s dental health.

Many rural areas, including Mullaithivu, have a shortage of dentists as the number of practicing dentists is found mostly in the urban areas.[18,21] Dental caries, as expected are less noticeable among children in communities with naturally occurring fluoride in the communal water. Residents of remote communities possess differing levels of knowledge and belief about oral health. Many did not have the means to clean or brush their teeth. They did not own a toothbrush nor did they care to clean their teeth.

SE status, such as family income and education, which may impact children’s dental health is considered as having an effect on oral health. The SE level in the estate life is at t poverty level and the average monthly income of the head of household is <50% of urban household income[23] and demonstrated from the DCS-household income and expenditure survey 2008. The presence of caries and untreated dental caries serves as the indicator of poor dental health.

It is hoped that preventive care and treatment of dental disease can be made more assessable to rural areas of Sri Lanka by increasing the number of dentists and other oral health-care providers. Implementing preventive oral health programs, including modifying behaviors to keep teeth healthy through regular brushing and a proper diet, are suggested. Instruction in oral hygiene and emphasizing the importance of oral care, incorporating it into the school curriculum by educating teachers as well as parents on the importance of good oral hygiene will help to eliminate potential dental problems due to lack of access to dental care. An oral health program could be made available and repeated at certain intervals for the prevention of ECC and to maintain good oral health for all children. The increased awareness of oral health will improve the dental and overall health of children and families in rural communities, especially in the tea sector. The drastic decrease in population in Mullaithivu from 2010 to 2019 needs to be evaluated, along with the effect oral health may have on general health. Oral health could be a contributing factor to poor general health. Ultimately, the goal is to provide oral health services to eliminate pain and suffering from oral and dental disease which could lead to more devastating health issues.

Social determinants associated with housing and individual concerns affect health. Poverty and poor labor conditions in the tea estate compounded by the low social-economic status of women workers and the lack of education in this community preclude their ability for upward mobility and improvement.

Further, disparities in oral health will remain because children from low income and poor families experience higher rates of dental caries and other dental-related problems. Providing outreach and service to underserved and vulnerable populations with enhanced education to include oral health will help to provide the necessary means to eliminate oral pain and disease and it would help to build healthier lives. Continued study with oral evaluations is encouraged to assist in the development of oral health programs for these suppressed areas.

Acknowledgment

No parts of this manuscript or abstract have been submitted for publication at any meeting or have been previously published.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Global oral health inequalities: The view from a research funder. Adv Dent Res. 2011;23:207-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The global burden of chronic diseases: Overcoming impediments to prevention and control. JAMA. 2004;291:2616-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. NIH. Oral Health in America In: A Report of the Surgeon General-Executive Summary. Rockville, Maryland, USA: DHHS, NIDCR, NIH; 2000.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789-858.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Social gradients in oral and general health. J Dent Res. 2007;86:992-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association between social determinants of health and functional dentition in 35-year-old to 44-year-old Brazilian adults: A population-based analytical study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2014;42:503-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inequalities in the frequency of free sugars intake among Syrian 1-year-old infants: A cross-sectional stud. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16:94.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighborhood social capital, neighborhood attachment, and dental care use for Los Angeles family and Neighborhood survey adults. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e88-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinduism in Sri Lanka. 2016. Available from: https://www.discoversrilanka.com https://www.statistics.gov.lk/religion [Last accessed on 2007 May 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- Housing and Labor Productivity of Female Tea Pluckers in Sri Lanka. Sandee Working Paper No.87-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- When Tear and Sympathy is Not Enough Living Wage for Sri Lankan's Plantation Workers. 2019. Available from: https://www.newsfirst.lk [Last accessed on 2012 Dec 16]

- [Google Scholar]

- Fighting Poverty, Sri Lanka's Tea Estate Workers Demand Pay Increase. In: Global Press Journal. 2017.

- [Google Scholar]

- Informing Relating to Population and Housing. Available from: https://www.statistics.gov.lk/statisticalhandbook

- [Google Scholar]

- Population by ethnicity and district according to Division Secretary 2012 In: Census Population and Housing 2011. Sri Lanka: Department of Census and Statistics; 2012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Basic Facts about General Hospital. Vavuniya, It is the Largest Hospital Under the Provincial Administration.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beyond the DMFT: The human and economic cost of early childhood caries. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:650-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Household Income and Expenditure Survey-2006/07 (Final Report) Colombo: Department of Census and Statistics; 2008.

- [Google Scholar]