Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and behavior on oral health in army personnels: A cross-sectional study

*Corresponding author: Gaushini Ramuvel, Department of Public Health Dentistry, H.P Government Dental College, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, India. gaushinirphd@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Ramuvel G, Bhardwaj V, Fotedar S, Thakur AS, Vashisth S, Sankhyan A, et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and behavior on oral health in army personnels: A cross-sectional study. J Global Oral Health. doi: 10.25259/JGOH_1_2025

Abstract

Objectives

Soldiers’ working environment is difficult, and they are supposed to withstand extreme conditions, so they cannot focus on hygiene, general health, or oral health. Maintaining optimal oral hygiene is crucial for all army personnel, whose physical fitness and operational efficiency are key components of their professional lives. The present study aims to assess the knowledge, attitude, and behavior of army personnel in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, regarding oral health.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted over a period of 6 months from June 2024 to November 2024. Army personnel who were present during the study and willing to participate were included, while those undergoing training, with medical conditions preventing participation, or unwilling to take part were excluded from the study. Permission was obtained from the Army Headquarters, ARTAC, Shimla, before the study began. The sample size was calculated to be 400. To evaluate participant’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding oral health, a standardized questionnaire was used.

Results

A total of 437 participants responded to the questionnaire and all the data were considered for the analysis. In our study, only 37.3% of participants knew very little about oral health, whereas 62.4% knew a lot. Out of all the participants, 43.4% had a favorable attitude about oral health, whereas 57.6% had a negative opinion. In terms of behavior, only 0.5% exhibited inadequate behavior, while 99.5% of participants have shown adequate oral health behavior.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable details on the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding oral health among army personnel in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. Most of them demonstrated a generally good level of knowledge and positive oral health behaviors, while some of the participants showed negative attitudes toward oral health. Significant gaps in understanding specific areas and some misconceptions were identified.

Keywords

Attitudes

Health behavior

Health knowledge

Military personnel

Oral health

INTRODUCTION

Oral health is an integral component of overall well-being and quality of life, often influencing an individual’s general health, productivity, and readiness to perform tasks.[1] Humans are most commonly affected by oral diseases. These diseases can never be eradicated due to their multifactorial origin and their association with social, behavioral, dietary, and other biological factors. Army personnel also constitute the same strata of the population.[2] Soldiers’ working environment is difficult, and they are supposed to withstand extreme conditions without proper food and shelter; thereby, they cannot focus on hygiene or general oral health. Dental caries is known to be associated with the lifestyle of the individual and attitude to health, which are closely related to the individual’s oral hygiene. The impact of dental caries can hamper an individual’s image, self-esteem, and social acceptance among peers.[3] Maintaining optimal oral hygiene is crucial for all individuals, including army personnel, whose physical fitness and operational efficiency are key components of their professional lives. However, knowledge, attitude, and behavior regarding oral health can vary significantly across different populations, including armed personnel. Various factors such as nutritional status, tobacco smoking, alcohol, hygiene, and stress are linked to a wide range of oral diseases, forming the fundamental basis for the common risk factor approach to prevent oral diseases.[4] A study by Chandar and Patankar, reported that 45.7% of them had healthy periodontium, 12.3% had bleeding gums, and caries experience was seen in 42.4%.[5] A study by Ahuja, observed that among the army personnel, both age groups 18-35 (30.9%) and 36-59 (55%) were smokers, and lichen planus was found in army personnel of age groups 18-35 and 36-59 years.[6]

An individual’s comprehension of the fundamental ideas involved in upholding proper oral hygiene and averting dental disorders is referred to as their knowledge of oral health. Knowledgeable people are better able to take preventive measures and adopt better oral hygiene habits, improving their mouth’s general health.[7] An individual’s oral health concern depends on a person’s attitude. An attitude is an organization of beliefs around an object, subject, or concept that predisposes one to respond in some preferential manner. People demonstrate a wide variety of attitudes toward teeth, dental care, and dentists. These attitudes naturally reflect their own experiences, cultural perceptions, familial beliefs, and other life situations, and they strongly influence oral health behavior.[8] The behavior of an individual depends on several factors that may influence individual and community health behavior, including knowledge, beliefs, values, attitudes, skills, finance, materials, time, and the influence of family members, friends, co-workers, opinion leaders, and even health workers themselves.[9]

Oral health is an essential part of achieving and maintaining readiness to deploy and fight. The dental health of military personnel has a significant impact on military operations since untreated oral conditions can result in an increased prevalence of dental disease and non-battle injury for deployed soldiers.[10] Any absence from duty will result in reduced efficiency of the organization. Dental diseases may impact the overall health and quality of life of an individual.[11] This warrants good general as well as oral health. However, on the other hand, military personnel are a group of professionals who have altogether a different working environment with 24-h duty and often being exposed to the highest physical strain and mental stress. This complicates their life and pulls down their level of living.[12]

Since the army personnel have irregular schedules, high-stress environments, and frequent relocation, poor oral health can affect overall well-being, physical fitness, and operational readiness. There is a lack of focused studies on the oral health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of army personnel in India. This study aimed to identify the gap in oral health knowledge, attitude, and behavior of army personnel toward oral health among army personnel in Shimla so that preventive strategies and improved dental care services can be planned. The aim of the present study is to assess the knowledge, attitude, and behavior on oral health in army personnel’s in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. The objectives were to assess the knowledge, attitude and behaviour on oral health in army personnel, assess the relationship between demographic factors and oral health, and to find the correlation between oral health knowledge, attitude and behaviour scores of army personnel.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted over a period of six months, from June 2024 to November 2024, to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding oral health among army personnel in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. The ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee with reference number HFW (GDC) B(12)50/2015-Voll-II- 2307. The study population comprised individuals currently serving at the Headquarters Army Training Command (HQ ARTRAC) as well as in Jutogh Cantonment in Shimla. Army personnel who were present during the study and willing to participate were included, while those undergoing training, with medical conditions preventing participation, or unwilling to take part were excluded from the study. Permission was obtained from the Army Headquarters, ARTAC, Shimla, before the study began. Participants were assured of confidentiality, and data were handled according to ethical research standards, used solely for this study. The questionnaire was distributed to the army personnel through a Google Forms link, allowing them to complete it electronically at their convenience. The questionnaire was administered to randomly selected participants using a simple random sampling method with probability proportional to size. Since there were approximately 200 personnel at HQ ARTRAC and 800 at Jutogh Cantonment, 25% of the sample was drawn from HQ ARTRAC and 75% from Jutogh Cantonment, ensuring proportional representation. The sample size was calculated to be 400 using the formula,

n = Sample size; Z = Standard deviation; p = Prevalence; q = (1-p); L = 0.05

= 384 ~ 400

The selected army personnel completed the questionnaire, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. To evaluate participant’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding oral health, Selvaraj et al., have given a validated questionnaire with 26 items.[13] The knowledge of oral health was evaluated using 11 questions that focused on maintaining and practicing oral health. The participants were asked if they knew the answer or if they did not. Correct responses received a score of 1, while incorrect responses received a score of 0. To assess the participants’ attitudes toward oral health, eight questions were asked. Five categories - highly agree, agree, disagree, no opinion, and strongly disagree - were applied to the responses. Strongly disagree or disagree were regarded as negative responses, whereas strongly agree, agree, and no opinion were regarded as good attitudes. The negative attitude received a score of zero, while the positive attitude received a score of one. There were eight questions on the survey used to evaluate the participant’s behavior toward oral health. Responses were divided into five categories: never, seldom, occasionally, very often, and always. The score for sufficient behavior was 1, while the score for deficient behavior was 0.[14]

Statistical analysis

The statistical software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 27 was used for all statistical analyses. The study employed both descriptive and inferential statistics. The Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to examine the relationship between oral health knowledge, attitude, behavior profile, and sociodemographic and habitual characteristics because our results did not match the presumptions. The correlation coefficient between oral health knowledge, attitude, and behavior was determined using Spearman’s rank correlation analysis. P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 437 participants responded to the questionnaire, and all the data were considered for the analysis. The participant’s sociodemographic profile is presented in Table 1. Every contestant was a male. Out of all the participants, 51.9% were between the ages of 18 and 38, and 47.6% were between the ages of 39 and 59. Among all the participants, 32% had a high school certificate, 33% had a post-high school diploma, and 35% were graduates or post-graduates. About 35.5% of the participants were skilled workers, followed by 32.1% who worked in clerical positions and 31.9% who were semi-professionals. Every participant was from the upper middle class and had a high income. According to the year of service, 21.9% of them had served for 11-15 years, followed by 20.5% who had served for 5-10 years, 19.8% who had served for 16-20 years, 19.1% who had served for 21-25 years, and 18.2% who had served for more than 25 years. Of the participants, 51.7% were married, while 47.8% were single. 48% of the participants reported to be smokers, while alcohol consumption was seen in 52.8%. Among all the participants, 33% were vegetarians, and 66.5% of them followed the mixed diet pattern.

| Demographic factors | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18-38 years | 228 | 51.9 |

| 39-59 years | 209 | 47.6 |

| Workplace | ||

| Artac, Shimla | 106 | 24.1 |

| Jutogh Cantt, Shimla | 331 | 75.4 |

| Education | ||

| High school certificate | 141 | 32.2 |

| Intermediate or post-high school diploma | 141 | 32.3 |

| Graduation or post-graduation | 155 | 35.3 |

| Occupation | ||

| Skilled worker | 156 | 35.5 |

| Clerical | 141 | 32.1 |

| Semi-professional | 140 | 31.9 |

| Income | ||

| ≥18229 | 437 | 100 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Upper middle class | 437 | 100 |

| Year of service | ||

| 5-10 years | 90 | 20.5 |

| 11-15 years | 96 | 21.9 |

| 16-20 years | 87 | 19.8 |

| 21-25 years | 84 | 19.1 |

| More than 25 years | 80 | 18.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 227 | 51.7 |

| Unmarried | 210 | 47.8 |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes | 211 | 48.1 |

| No | 226 | 51.5 |

| Alcohol | ||

| Yes | 232 | 52.8 |

| No | 205 | 46.7 |

| Diet | ||

| Vegetarian | 145 | 33 |

| Mixed diet | 292 | 66.5 |

All values are expressed as frequency with percentages

The participant’s knowledge, attitudes, and behavior about oral health are summarized in Table 2. They demonstrated an excellent awareness of subjects such as the dentition condition, the function of bacteria in gingival tissues, and the connection between tobacco use and oral cancer. They were unaware of information on dental plaque, deciduous tooth decay, and the necessity of tooth movement to address anomalies. Many participants had misconceptions regarding scaling, the dentist’s involvement in disease prevention, and the advantages of fluoridated toothpaste despite their good attitudes toward brushing and oral health. Although most of them brushed twice a day and went to frequent checkups, their conduct was generally decent. However, many of them chewed their food improperly, suffered tooth sensitivity, and had toothaches. In our study, only 37.3% of participants knew very little about oral health, whereas 62.4% knew a lot. Out of all the participants, 43.4% had a favorable attitude about oral health, whereas 57.6% had a negative opinion. In terms of behavior, only 0.5% exhibited inadequate behavior, while 99.5% of participants have shown adequate oral health behavior [Table 3].

| S. No. | Questions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Questions on knowledge toward oral health | Good knowledge | Poor knowledge | |

| 1. | There are two sets of teeth during lifetime | 269 (61.3) | 168 (38.3) |

| 2. | Tooth infection causes gum bleeding | 221 (50.6) | 216 (49.4) |

| 3. | Replacement of missing tooth improves oral hygiene | 356 (81.5) | 81 (18.5) |

| 4. | The dental caries of deciduous teeth need not be treated | 96 (22) | 341 (78) |

| 5. | Bacteria is one of the reasons to cause gingival problems | 325 (74.4) | 112 (25.6) |

| 6. | Fizzy soft drinks affect the teeth adversely | 355 (81.2) | 82 (18.8) |

| 7. | Loss of teeth can interfere with speech | 399 (91.3) | 28 (8.7) |

| 8. | Irregularly placed teeth can be moved into correct position by dental treatment | 105 (24) | 332 (76) |

| 9. | Decayed teeth can affect the appearance of a person | 411 (94.1) | 26 (5.9) |

| 10. | Tobacco chewing, or smoking can cause oral cancer | 432 (98.4) | 5 (1.1) |

| 11. | White patches on teeth are called dental plaque | 7 (1.6) | 430 (98.4) |

| Questions on attitude toward oral health | Positive attitude | Negative Attitude | |

| 12. | Keeping your teeth clean and healthy is beneficial to your health | 369 (84.4) | 68 (15.5) |

| 13. | Scaling is harmful for gums | 148 (33.9) | 289 (66.1) |

| 14. | Dentists care only about treatment and not prevention | 138 (31.6) | 299 (68.4) |

| 15. | Sweet’s retention leads to tooth decay | 137 (31.4) | 300 (68.6) |

| 16. | Brushing with fluoridated toothpaste prevent tooth decay | 69 (15.8) | 368 (84.2) |

| 17. | Brushing teeth twice a day improves oral hygiene | 362 (82.8) | 75 (17.2) |

| 18. | Gum bleeding denotes gum infection | 205 (46.9) | 232 (53.1) |

| 19. | Improper brushing leads to gum disease | 423 (96.8) | 14 (3.2) |

| Questions on behavior toward oral health | Adequate | Inadequate | |

| 20. | I have bleeding gums during brushing | 317 (72.5) | 120 (27.5) |

| 21. | I do routine dental check-up | 397 (90.8) | 40 (9.2) |

| 22. | I give importance to my teeth as much as any part of my body | 434 (99.3) | 3 (0.7) |

| 23. | I brush my tooth twice daily | 395 (90.4) | 42 (9.6) |

| 24. | I use teeth to open cap of bottled drink | 412 (94.3) | 25 (5.7) |

| 25. | I have sensitive teeth | 366 (83.8) | 71 (16.2) |

| 26. | I experience tooth ache while chewing food | 333 (76.2) | 104 (23.8) |

All values are expressed as frequency with percentages (in parentheses)

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | ||

| Good | 274 | 62.4 |

| Poor | 163 | 37.3 |

| Attitude | ||

| Positive | 184 | 43.4 |

| Negative | 253 | 57.6 |

| Behavior | ||

| Adequate | 435 | 99.5 |

| Inadequate | 2 | 0.5 |

All values are expressed as frequency with percentages.

Table 4 displays the relationship between the participants’ oral health knowledge, attitude, behavior, and sociodemographic and habitual characteristics. The relevance of age, marital status, education, occupation, years of service, smoking, alcohol usage, nutrition, and workplace varied. Those aged 18-28 had a knowledge mean of 6.71, and those aged 29-59 had a mean of 6.85, and no statistically significant differences were present. Smokers scored slightly lower on knowledge and behavior scores than non-smokers and it was not statistically significant. No statistically significant differences were present between alcohol consumption and knowledge, attitude, and behavior scores. However, attitude and behavior were associated with marital status, with unmarried participants exhibiting lower behavior scores but more positive attitude scores among married personnel. Graduates exhibited more positive attitudes toward oral health. Years of service and occupation did not significantly associate with knowledge, attitude, and behavior scores. No significant associations were present between occupation or diet patterns and knowledge, attitude, and behavior scores.

| Variable | Categories | n | K-Mean (mean±SD) | P-value | A-Mean (mean±SD) | P-value | B-Mean (mean±SD) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group** | 18-28 years | 228 | 6.71±1.27 | 0.258 | 4.29±1.21 | 0.459 | 6.11±0.88 | 0.474 |

| 29-59 years | 209 | 6.85±1.33 | 4.17±1.16 | 6.03±0.96 | ||||

| Smoking** | Yes | 211 | 6.74±1.32 | 0.509 | 4.30±1.16 | 0.102 | 6.01±0.93 | 0.183 |

| No | 226 | 6.88±1.28 | 4.17±1.21 | 6.12±0.90 | ||||

| Alcohol** | Yes | 232 | 6.76±1.33 | 0.455 | 4.26±1.12 | 0.658 | 6.06±0.91 | 0.663 |

| No | 205 | 6.88±1.26 | 4.20±1.26 | 6.09±0.93 | ||||

| Marital status** | Yes | 227 | 6.77±1.35 | 0.222 | 4.05±1.21 | 0.002# | 6.15±0.89 | 0.044# |

| No | 210 | 6.87±1.25 | 4.43±1.14 | 5.98±0.94 | ||||

| Education* | High school | 141 | 6.95±1.32 | 0.083 | 4.29±1.21 | 0.008# | 6.16±0.91 | 0.349 |

| Post high school | 141 | 6.71±1.26 | 3.99±1.15 | 6.06±0.89 | ||||

| Graduate | 155 | 6.77±1.33 | 4.41±1.16 | 6.01±0.95 | ||||

| Occupation | Skilled worker | 156 | 6.68±1.26 | 0.368 | 4.13±1.22 | 0.285 | 6.06±0.87 | 0.425 |

| Clerical | 140 | 6.92±1.29 | 4.34±1.20 | 6.15±0.89 | ||||

| Semi-professional | 140 | 6.86±1.34 | 4.25±1.12 | 6.03±0.99 | ||||

| Year of service* | 5-10 years | 90 | 6.84±1.19 | 0.371 | 4.16±1.04 | 0.144 | 5.91±0.96 | 0.283 |

| 11-15 years | 95 | 6.83±1.44 | 4.24±1.24 | 6.15±0.93 | ||||

| 16-20 years | 87 | 6.56±1.35 | 4.29±1.27 | 6.13±0.93 | ||||

| 21-25 years | 84 | 6.95±1.15 | 4.01±1.14 | 6.12±0.93 | ||||

| More than 25 years | 80 | 7.01±1.32 | 4.49±1.21 | 6.05±0.81 | ||||

| Diet* | Vegetarian | 145 | 6.87±1.34 | 0.716 | 4.26±1.08 | 0.924 | 6.12±0.91 | 0.379 |

| Nonvegetarian | 141 | 6.72±1.33 | 4.23±1.19 | 6.00±0.88 | ||||

| Mixed diet | 151 | 6.86±1.23 | 4.22±1.29 | 6.09±0.96 | ||||

| Work place | Artac | 106 | 6.74±1.34 | 0.372 | 4.30±1.21 | 0.687 | 6.08±0.94 | 0.908 |

| Jutogh | 330 | 6.84±1.29 | 4.21±1.18 | 6.07±0.91 |

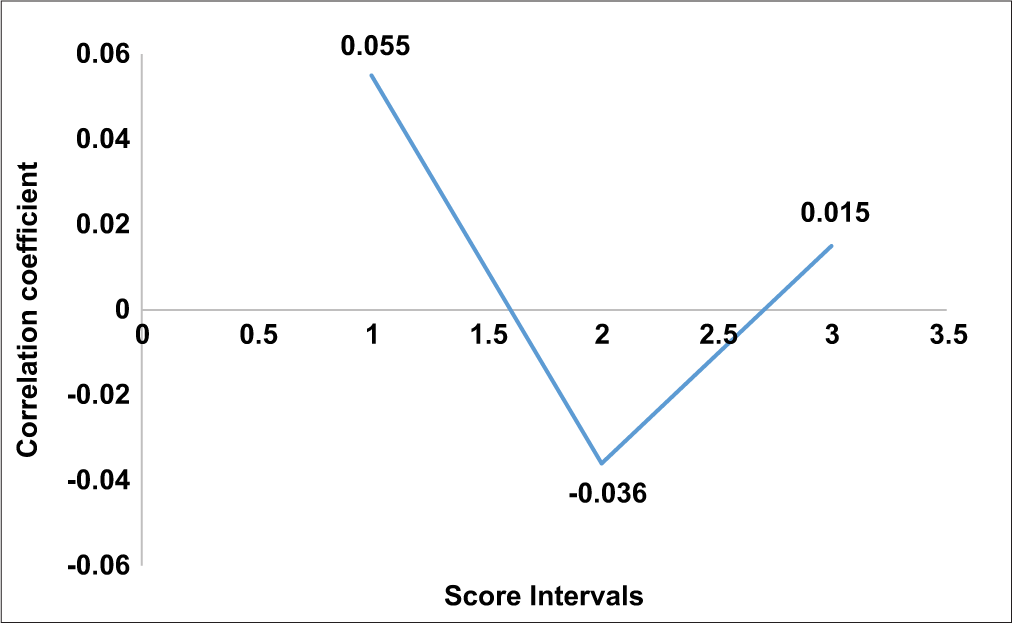

No significant correlations were found between knowledge, attitude, and behavior regarding oral health, as shown in Graph 1. Attitude and knowledge scores were positively correlated, and a negative correlation was found between behavior and attitude. Similar correlations were seen between behavior and knowledge scores as well.

- Correlation between oral health knowledge, attitude, and behavior scores of adult population.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first of its kind to evaluate army personnel’s oral health-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. As far as we are aware, no prior research has documented comparable findings in this particular demographic or geographical setting. In our study, all the participants were male, which aligns well with the study by Datana,[11] where 85% of the participants were male, and Asif et al.,[2] 99.7% of them were male. The high prevalence of males is reported because, in a country like India, males are generally recruited more in the Indian Armed Forces. Most of the participants were between the ages of 18 and 38, which constitutes 52%. This is in contrast to the study by Datana, where 91% were between the ages of 41 and 50.[11] Among all the participants, 35.3% were graduates and postgraduates. Our findings were in contrast to those of the study by Datana, where 66% of the participants were graduates and 29% were postgraduates.[11] In our study, 48.1% were smokers, and 52.8% of them had the habit of alcohol consumption since army personnel are supposed to smoke and consume alcohol in social gatherings.

Most participants understood fundamental oral health concepts, such as the part bacteria play in gum disease, the significance of tooth replacement, and the detrimental consequences of smoking and tobacco use on oral health. Besides these knowledge gaps were still found, especially about managing dental caries in deciduous teeth, the function of dental plaque, and the significance of orthodontic therapy for teeth that are positioned abnormally. In our study, 62% of the army personnel had good knowledge of oral health, in accordance with the results shown in a study by Fernandes, where 68% of the US army personnel had good knowledge of oral health.[15] Similar results were also reported by Datana, where the personnel of the Indian Armed Forces have shown good knowledge scores (4.55 ± 0.46).[11] Selvaraj et al., also reported similar results and good knowledge (97.7%) toward oral health among south Indian adult populations.[14]

Our study found that a negative attitude (57.6%) was comparatively higher than a positive attitude (43.4%) toward oral health among army personnel. Even though some participants recognized the importance of brushing and oral hygiene, many held misconceptions, such as the belief that scaling harms the gums and that dentists play a minimal role in preventing oral diseases. These misconceptions can hinder effective oral health practices. In contrast to it, Datana reported good attitudes toward oral health among army personnel (4.56 ± 0.54).[11] Our results follow Selvaraj et al., who reported an inadequate attitude of the South Indian adult population toward oral health.[14]

The behavior of the participants regarding oral health was largely positive. Most army personnel practiced adequate oral hygiene, with most brushing twice daily and undergoing regular dental check-ups. This reflects a generally strong commitment to maintaining oral health. However, certain risky behaviors, such as using teeth to open bottle caps and a high prevalence of tooth sensitivity and toothaches while chewing, indicate areas where behavioral interventions are needed to reduce the risk of oral injury and dental complications, whereas Selvaraj et al., reported inadequate behavior toward oral health among South Indian adult populations.[14]

Sociodemographic and habitual factors did not show a significant association between most variables and oral health knowledge, attitudes, or behavior. While younger participants showed slightly lower knowledge scores compared to older ones, the possible reason could be younger individuals prioritize general health rather than specifically focusing on oral health. Among all the participants, unmarried personnel had more positive attitudes than married personnel; these associations were not strong. This could have been because unmarried individuals might have more time to focus on oral health. Habits such as smoking and alcohol consumption did not have a significant impact on oral health knowledge, attitudes, or behavior since awareness exists, but the perceived risks of these habits may be underestimated.

The correlation analysis revealed a non-significant weak positive correlation between knowledge-attitude (r = 0.055; P = 0.25) and knowledge-behavior (r = 0.015; P = 0.76), and weak negative correlation was seen between attitude-behavior (r = −0.036; P = 0.45) which was similar to the findings reported by Selvaraj et al., where non-significant correlation was seen between knowledge-attitude (r = 0.11, P < 0.21), knowledge-behavior (r = −0.037, P < 0.68), as well as attitude-behavior (r = 0.01 P < 0.91) among south Indian population.[14]

Overall, the army personnel in Shimla demonstrated good oral health behavior, but knowledge and attitude scores were not satisfactory. Addressing the gaps in knowledge and correcting false attitudes is essential to enhance their overall oral health outcomes. Regular and targeted oral health education, mainly focusing on professional care, preventive practices, and avoiding risky habits, is likely to improve both attitudes and behavior over time. This study also highlights the importance of occupational and environmental factors in military settings that influence oral health practices and outcomes.

The study has a few limitations. It relies on self-reported data, which may introduce bias, as participants could overstate their practices. The findings are specific to male army personnel in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, limiting generalizability to other populations or regions. Moreover, the study focused on quantitative assessments without incorporating qualitative insights.

Future research should consider involving all the personnel, including female personnel of the Indian Armed Forces, using longitudinal designs to monitor change over time, and implementing qualitative methods to find particular risk factors associated with negative attitudes toward oral health. The integration of oral health assessment with broader health indicators such as stress levels and dietary habits can also provide a more comprehensive understanding of contributing factors.

CONCLUSION

This study successfully highlights the oral health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among army personnel in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. Most of them demonstrated a generally good level of knowledge and positive oral health behaviors, while some of the participants showed negative attitudes toward oral health. Significant gaps in understanding specific areas and some misconceptions were identified. By addressing these gaps and misconceptions, it is possible to improve oral health outcomes and promote better dental hygiene practices among army personnel.

Ethical approval

The research/study approved by the Institutional Review Board at H.P Government Dental College Shimla, number HFW(GDC)B(12)50/2015-Voll-II-2307, dated May 31, 2024.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Oral health status and treatment needs of police personnel in Mathura city. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:51-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- The oral health status among army personnel in Patna Bihar-A descriptive cross sectional study. Int J Oral Health Dent. 2020;6:27-35.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oral health practices related risk factors and prevalence of dental caries in Armed Forces: A multicentric study. MJAFI. 2024;80:475-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The common risk factor approach: A rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:399-406.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of oral diseases status and treatment needs between armed forces personnel and Karnataka police service in Bengaluru city. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2014;12:268.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oral health status, treatment needs and examination of dental standards of army recruits at Belgaum. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2011;9(Suppl 2):S714-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dental caries and oral health behaviour in the Malaysian Territorial Army Personnel. Arch Orofac Sci. 2011;6:19-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Children's preventive dental behavior in relation to their mothers' socioeconomic status, health beliefs and dental behaviors. ASDC J Dent Child. 1986;53:105-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preventive medicine in obstetrics, pediatrics, and geriatrics In: Park's textbook of preventive and social medicine. Jabalpur: Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers; 2000. p. :605.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oral health survey of military personnel in the Phramongkutklao Hospital, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92:S84-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantitative study of knowledge, attitude, and practice of oral health among officers in the Indian Armed Forces: A cross-sectional survey. J Dent Def Sect. 2024;18:3-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing a standardized oral health survey for the tri-services. Mil Med. 1994;159:179-86.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Development and validation of oral health knowledge, attitude and behavior questionnaire among Indian adults. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:68.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological factors of periodontal disease among South Indian adults. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022;15:1547-57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral health practices, knowledge and attitudes amongst United States army active duty enlisted soldiers (Doctoral dissertation, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland. 2019:2-9.

- [Google Scholar]